The country sound is so much better than the lyrics

Recently I read an essay by Irish journalist Nuala O’Faolain about how Irish people love country music. While admitting to its powerful emotional appeal, she humorously deconstructs its tropes, which chronicle a simple world where “men are men and women are sweet and helpful angels whose main task here on earth is to stand by their man and help him through the night.” [A Radiant Life]

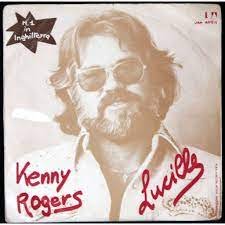

I was immediately reminded of the popular Kenny Rogers song Lucille. The lyrics bother me. Seemingly aware of the rigid C&W sex roles, Rogers has attempted to turn the stereotype on its head. However, I find it impossible to suspend my disbelief in the character of Lucille.

Let’s review the ballad’s plot. A man arrives in “a bar in Toledo.” He admires a pretty woman who is drinking alone. When she takes off her wedding ring, he goes over to chat her up, believing he’s in with a chance. Tongue loosened by alcohol, Lucille claims she’s “no quitter.” This is patently untrue. In the next breath, she admits to being weary of her life, “hungry for laughter” and seeking “whatever the other life brings.”

At this point, Lucille’s husband comes in. Seen in the mirror, the big man with the calloused hands “looks out of place.” When he approaches, the narrator expects a fight. Instead the guy ignores him and berates his wife for leaving him with “four hungry children and a crop in the field.” His comments suggest this is not their first fight. In a blatant effort to make her feel guilty, he tells her “this time your hurtin’ won’t heal.”

Venture below the literal level, we may find the image of plowing a field suggestive. Could there be a sub-plot? If Lucille’s husband has been plowing another field, that would make her defection slightly less bizarre. Even so, it’s hard to credit that she wouldn’t even make the children’s dinner before heading off to the bar to pick up a stranger.

We don’t learn whether or how Lucille responds to her husband’s accusations. All we are told is that she drinks more whiskey, then silently accompanies the stranger to “a rented motel room.” I admit that a part of me wondered why he picked her out as such a beauty. She’s a veteran for four births and the associated child care — at least until she left them just before dinner time.

Instead of the obvious ending, we get a surprise. As the couple walk toward the motel, the narrator thinks back on how Lucille made her hulking husband “look small.” Quite a feat. Besides, it’s her behaviour that looks small - or at least deeply strange. Be that as it may, the sympathy of the narrator now shifts to the husband, whose accusations keep repeating in his head. At the critical moment, he finds himself unable to “hold her.” True, they’ve both had generous amounts of whiskey. Yet we are given to understand that he loses his desire for her out of male solidarity with the husband’s damaged pride and sensibility.

To fully comprehend a work of art, it helps to know the context. This song was written in 1976, when Rogers was about 38 — meaning he came of age before the so-called “women’s liberation” movement began. What are we to make of this? The kind interpretation would be that he sympathizes with his female protagonist for wanting “whatever the other life brings.” But I can’t buy it. There’s no getting round the fact that Lucille comes off as the villain, while her ex is an injured (albeit sulky) hero.

True, the stranger might be an unreliable narrator. But even if that’s true, the plot doesn’t resonate. Show me a woman with four kids who ups stakes, leaves husband and children, goes to the local bar and ostentatiously takes off her wedding ring in front of a bunch of male drinkers, looking to pick one of them up. If a real woman did that, there would have to be more going on than her boredom with “living on dreams.” Addiction, maybe, or mental health issues.

One final question. Why, after asking her name, does this narrator continue to refer to her generically as “the woman?” This seems particularly galling when he obviously has designs on her.

But let’s approach this another way: would the song work if the roles were reversed? Here’s a possible start:

You chose a fine time to leave me, LukeyThree hungry children and a babe on the way.You've been a sad boy, sometimes a bad boy,But still how I wish you would stay.Does this have the potential to be more believable? You be the judge.