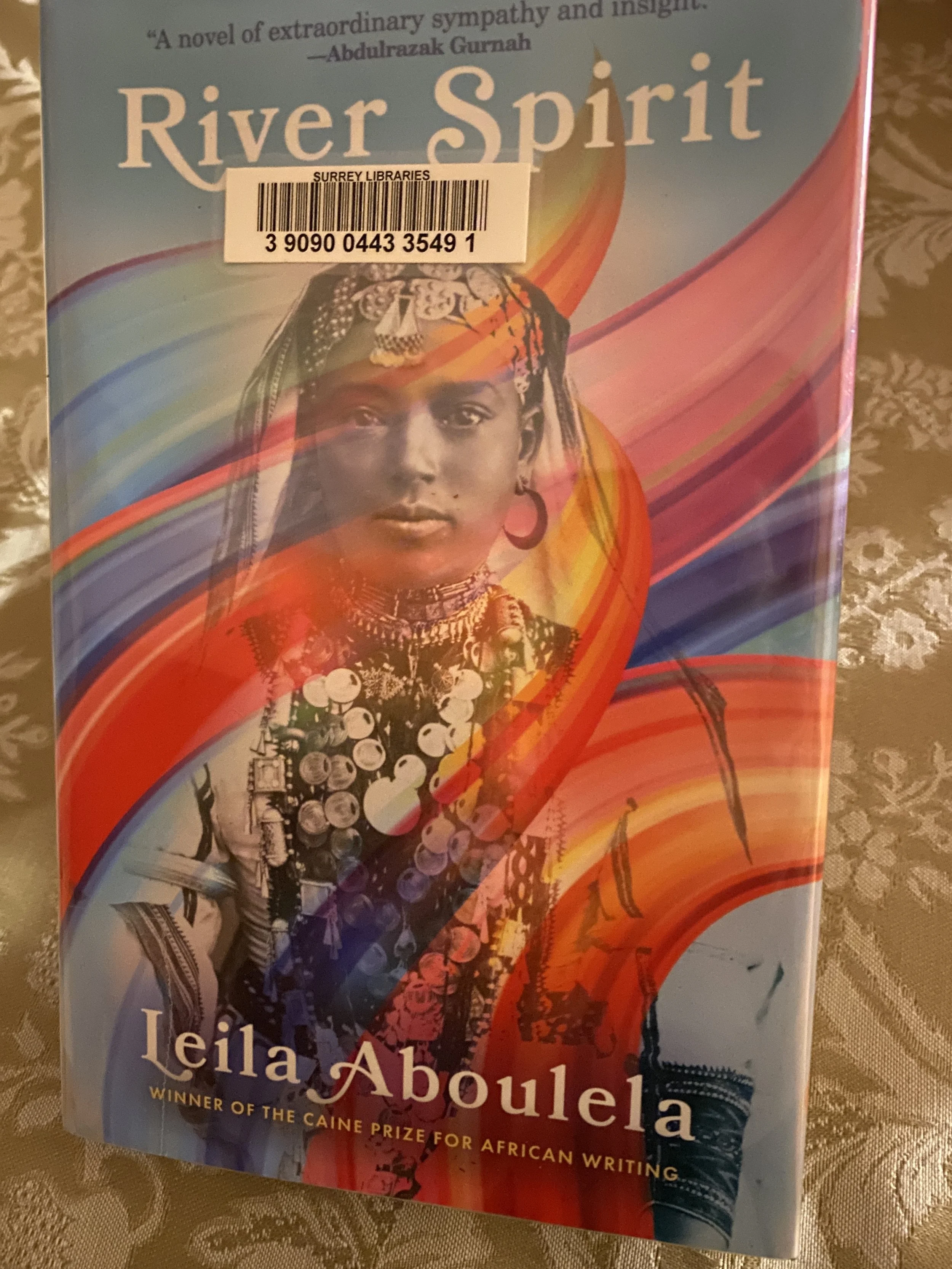

River Spirit by Leila Aboulela

Set in Mahdist Sudan in the late 1800s, this novel carries us into the heart of the Muhammad Ahmad’s rebellion against foreign control of the region. A deeply divisive figure among Muslims, the Madhi claimed to be the Expected One, then rebelled against the British, Egyptians and Ottomans who were controlling Sudan at the time. After his death, the Mahdi’s tomb in Omdurman was desecrated by the British to discourage another Muslim uprising. It was later rebuilt.

We witness this vicious and divisive religious and colonial war through the eyes of the author’s imagined characters — local women and men of different classes and varied ethnicities.

We are also shown Sudan through the eyes of a Scottish artist whose character seems loosely based on Orientalist painter David Roberts, and from the author’s imagined perspective of the British General Gordon, who was killed by Mahdist rebels while awaiting promised relief troops in Khartoum.

At the centre of the story is Akuany, later renamed Zamzam. Orphaned as a child, she and her young brother are rescued by the acacia gum trader from their sacked village on the Blue Nile and taken to Khartoum on his camel. During this journey, the girl develops a deep attachment to Yaseen and forms a conviction that they will never be separated. Neither has any idea of the tribulations they will each have to face.

Yaseen is determined to study and improve himself. A natural scholar, he travels to Cairo to obtain his education at Al Azhar University, then returns to Khartoum. Educated, intelligent, and a devout Muslim, he maintains his integrity, remaining unable to accept the Mahdi as the Expected One sent by Allah. His refusal to join the rebels carries heavy consequences. Yet even at his lowest point, he maintains his courage. “We are entrusted with health or security or wealth or position or family or skills or children or all these things and then expected to do our best.” When someone asks him whether it is acceptable to pretend to join the Mahdi’s cause if the alternative is to be killed, Yaseen is not quick to answer, as he reflects that “The layman always expects us to answer in binaries—halal or haram, permissible or impermissible.”

Musa is an utterly different character. From a poor family, he despises his father, a maker of knives and spears who routinely beats his wife and sons. A poor student, Musa cannot tell left from right or learn his letters and often skips school to avoid being constantly berated and beaten. A directionless youth without skill or ambition, he is spurned by a girl from a higher family, and takes to drinking. The Mahdi recognizes this young man as a perfect recruit. Talking to Musa with “graces and smiles,” he soon persuades him into the rebel army. Ever obedient to the man who “saved” him, Musa is ready to carry out any and all instructions from the Mahdi, who uses this man’s violent rage for warlike purposes, even as he pays lip service to peace.

Sahla is a rarity in the society of the time, an educated woman. Schooled with her brothers in youth, she does not defer to men but converses with her husband on an equal footing. She is kind and loving to those around her. Strong in adversity, she thinks ahead and makes carefully considered sacrifices for the safety and well being of the people she loves. Seen through Zamzam’s eyes, Sahla is impressive, someone who “grew up safe in a father’s house,” was given a trustworthy husband, and passed through life “protected and firm.” Zamzam marvels that Sahla had “never been whipped, never been violated…never been cowed, pushed or starved.” She observes the ease in the other woman’s body, so unusual is it to see someone who “bows down only in prayer or to look at her books.“ Sahla can distinguish religion from politics and recognizes the Mahdi’s violent rebellion for what it is. Greatly oppressed during the dark times, she manages to carry on, living in hope that dawn will surely come.

In addition to the gripping story, this book offers a wealth of images about the places portrayed. Through the eyes of the painter Roberts, we are given a rich sense of the Khartoum of the time. Built by the Ottomans to facilitate trade, the city contains “a swirl of nationalities. Locals in flowing white robes. Blacks in more colourful ones, Arabs…from Morocco and Libya, Austrians, Armenians, South Africans employed in the Egyptian foreign service, a Jewish community of Europeans and non-Europeans” speaking Arabic, German, Greek, Swahili and Turkish. Roberts is greeted “with the wild cries of the birds at dawn and the verdant garden of the Roman Catholic mission full of banana and fig trees, mimosa and jasmine bushes.” Water wheels and water jugs, “palm trees and parrakeets, sandalwood and sailing boats.” In his garden, he is surprised to see monkeys, and enjoys a private well. Walking home along the river, he looks at the storks and ibises and is astonished by the sighting of a hippopotamus. Roberts also looks at the people in their “medley of clothes—Sudanese jellabiya, tarbush with European suit, traditional Turkish, traditional Egyptian, Shilluk men from the south with little more than a loincloth.”

Other images that stayed with me were the customs of singing to the camels and sleeping in their shade. We learn of a violent desert wind called the haboob, “a whorl rising from the ground, orange, dark yellow, brown, whipped by its own frenzy, propelled by it’s own energy,” laden with sand and dust.

Aboulela brilliantly unpacks the social history of the era, often tender and surprising, yet running against a constant background of routine violence, sexism, social inequality and brutal religious intolerance. To encourage propriety among his followers, the Mahdi and his appointed generals, lieutenants and tribal chiefs mete out punishments for insults. “Calling a fellow Muslim a dog or a pig or a Jew warranted eighty lashes and seven days of confinement. Twenty-seven lashes were the punishment for a woman with uncovered hair or one who spoke with a loud voice.”

Slavery, though illegal, is still practiced in some places where those in authority turn a blind eye. A young girl working for the governor has her virginity “taken by a binbashi,” who assumes it is a gift “included in the governor’s hospitality.” Assigned a new Muslim name to suppress her eastern tribal identity, Zamzam is sent to work in the governor’s residence, where she is “embedded in the world of the kitchen and the guest quarters” without anyone considering her own wishes or ambitions. Even when she is bought back from slavery, the transaction takes place without her knowledge or consent.

Years pass before she learns the meaning of her assigned name. When she does, she’s delighted to learn she’s been named after a sacred well in Mecca, a reminder of water and her love of the river that flows through her faraway homeland.

Zamzam watches the steamers that finally come to relieve the beleaguered Khartoum, but it is too late. Seeing that the city has fallen to the Mahdi’s forces, the ships turn in the river and go back downstream. “From the British perspective,” she reflects bitterly, “the citizens of Khartoum were not worth saving; it had never been about them.”

When I googled General Gordon, the first listing that came up was an elementary school named after him in the city of Vancouver.